This article was originally published in the Wongs’ Association Convention magazine in 2011 as part of an exploration of Chinese in Canada history. You can also download the article as a PDF (2.3Mb).

Climbing the narrow staircase to the Wongs’ Association’s third floor office in downtown Toronto, past the plaque reading Wong Kung Har Wun Sun Association in Chinese and English, you reach a nondescript door that gives no hint of what lies beyond. When the association bought the building in 1979 the entire top floor was redesigned and the space opened up. Along with offices and a small kitchen, it now accommodates a large assembly hall with a 20′ ceiling where the shrine to the Wong ancestors stands in gilded solemnity, lit from above by large windows encircling the raised roof — itself a first in the neighbourhood. So, past the door you walk into a burst of natural light — even on a rainy day.

Arriving at the Wong’s Association

Tuesday afternoon at the end of March might seem an unlikely time to find anyone at here, but my visit is at the invitation of Chuck K. Wong, a director of the Association for more than a decade. He is on duty today, one of a roster of volunteers who make sure “there’s always someone here to let members in.”

He shows me around, pointing to the Wong family tree and the photographs of Association members that line the hallway, and the place of honour inside the Hall for the photos of the Association chairmen going back to the 1950s.

A Tase of Chinese Canadian History

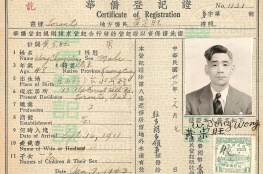

He relates the story of the ancestor commemorated here (one of 21 sons of the original patriarch) and gives me a thumbnail sketch of the history of the Association and its two antecedent organizations. The original members were Toishanese, and given the small Chinese community living in Toronto during the Exclusion years (1923-47), their numbers dwindled. “To strengthen the association we needed more members, so other Wongs were invited to join us,” he explains.

His knowledge, he tells me, comes largely from conversations; what he knows is what elders have told him over the years. So he worries about losing these memories before the history of the Association has been properly recorded.

What’s on Chuck K. Wong’s mind, though, is not the past but the up-coming tri-annual national convention which will bring Wongs from around the world to Toronto for three days in August. He sees the event as an opportunity for re-engagement.

An International Gathering

The international dimension of the clan’s experience is a key part of the Wong heritage. Emigration has produced an astonishing diversity in the name itself, he notes. It has also, obviously, nurtured a skill for negotiating cultures, not to mention foreign languages and customs. Two characteristics seem to be key. First the tendency of Toishanese to treat each other as family, and to believe in the ethic of helping one’s own and sharing resources.

So, from the beginning the community reached beyond the Chinatowns across the country into small towns and remote places like Moose Factory creating a web of relationships built up between relatives and friends that enabled people to survive.

Secondly, there was the clan’s reputation for honouring its word. The Association, for example, set up a committee which operated like a credit union, providing seed money for members when no bank would. “There was nothing on paper. It was all on people’s word, ” Mr. Wong emphasizes repeating the old adage: “When you deal with a Wong, nothing can go wrong.”

A Valuable Community

Mr. Wong was himself inspired by his great uncle Wong Nan Yao, the third chairman of the Wong Kung Har Wun Sun Association who first took him to the Association, and who always spoke of the importance of contributing to the community, and giving back. Times change, and today the Association may no longer be the social and economic lifeline it was, but the value of community has not disappeared.

A week later, on a Saturday afternoon, we pull up to Greg K.W. Wong’s house and find him working in the garden, eagerly making up for the long delay of Spring. He is part of the convention committee whose work is well underway at this point.

We chat in his spacious kitchen, my friend Chuck C.C. Wong, who brought me along, has taken on the task of putting the convention booklet together. Greg K.W. Wong regularly hosts sessions like this at his house — and very soon in his back garden, too — and clearly knows a lot of people. He recruits individuals who want to make something happen, and charges them with doing just that.

An affable man, he welcomes participation and delegates decision-making. So the cast of volunteers gathers numbers like a chain letter.

Greg K. W. Wong also sees history as instructive. However, there will be no dwelling on the past at the convention. “The intention is to encourage young people to ask themselves what they’d like to achieve, not to encourage them to carry chips on their shoulders.” Like Chuck C.C. Wong, he worries about the history that is locked up in memory, including those stories never spoken of. And he also speaks of the necessity of collaborative action.

He tells the story of how during the Exclusion years, when racism was virulent and the Chinese were barred from public places like trains, hotels and swimming pools, people would travel from Chinatown to Chinatown via an “underground railroad” of safe houses. This was how the community worked, looking after its own. And to this day, if you stop of at a local Chinese restaurant you are likely to be greeted as family.

The power of association has to do with numbers, but it also has to do with the sharing skills and knowledge. It can be a source of individual self-knowledge, and self-confidence. “Given the history of the Wongs in Canada, and our contributions to the country, to be a Wong today means being equal to all and second to none.”