Shortly after I arrived at Kogawa House, artist Laura Bucci came for an evening session of button making. She arrived with several plastic packing boxes filled with an array of coloured and patterned paper, old magazines, scissors, glue, and a collection of rubber stamps with words like “escape” and “passion” on them. The event was part of Word on the Street, which expanded this year to three days over the weekend, and to off the traditional site at the Central Library to community venues like Kogawa House.

We set up a table in the living room and over the evening about twenty-five people set to creating their own “designer” buttons. The best part, naturally, was the moment you got to slip your creation onto its metal backing with Laura’s neat little hand-press, and pop out the result.

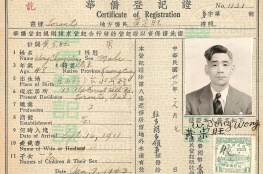

That evening I also met Howe Chan. Howe contacted me last November just after I returned from China. I’d been to Taishan, the county in Guangdong which many Chinese Canadians came from, looking for the story of a head tax payer named Wong Dong Wong who left China for Canada in 1911. The Saturday before I left for Beijing, Sing Tao published a front page story about my search. Howe, who happened to be in Taishan himself at the time, saw the story when he returned home, got his daughter Jennifer to sleuth down my phone number, and called me up.

“If only I’d known,” were practically his first words. “I was there in Taishan right at the same time, and could have taken you to his village.” My own visit had yielded the fact that Mr. Wong was an orphan whose father died the same month he was born in 1895, and his mother a few months later. Mr. Wong was brought to Gold Mountain by an uncle to work in the business he was setting up with two others in South Vancouver. Howe grew up in a village very close to Wing Ning where Mr. Wong was born, and knows it well. As a boy he often fished in the river that runs in front of it, and remembers going there at lunar New Year with his mother to see Cantonese opera.

I began sending Howe copies of material I’d gathered. The official Wong family tree from the Bureau of Overseas Chinese and Foreign Affairs, and the family’s own handwritten genealogy that dates back to the 1870s shown to me by the grandson of Wong Wanshen, the uncle who sponsored Mr. Wong. In return Howe sent me copies of histories he written about the Chen family, and montages of photos and maps of Taishan with detailed notations written in a very precise and clear hand. Howe does not do computers, so over the year we sent stuff back and forth through the mail, and had long conversations on the phone.

Howe is now my chief advisor on all things to do with Shui Doi – the name of Wing Ning in the local dialect. But since meeting him in person and getting to know him, I have also heard more about his story, and the hardship of his mother in particular. Separated from her husband for decades she was forced to live out her life alone in China. For in 1946, despairing of ever reuniting, Howe’s father had married in Canada. The very next year the exclusion laws were lifted.

Today, Howe leaves for another trip back to his village. He’s undertaken to visit Shui Doi and to see what else he can find out about Mr. Wong. By this time, too, he has discovered his own connection to Wong’s story. There in the family tree he discovered his own mother,a cousin of my Mr. Wong, five times removed but in the same generation.

I’ve always been aware that Canada is a small country. I didn’t realize that China, in some ways, is a small place, too.