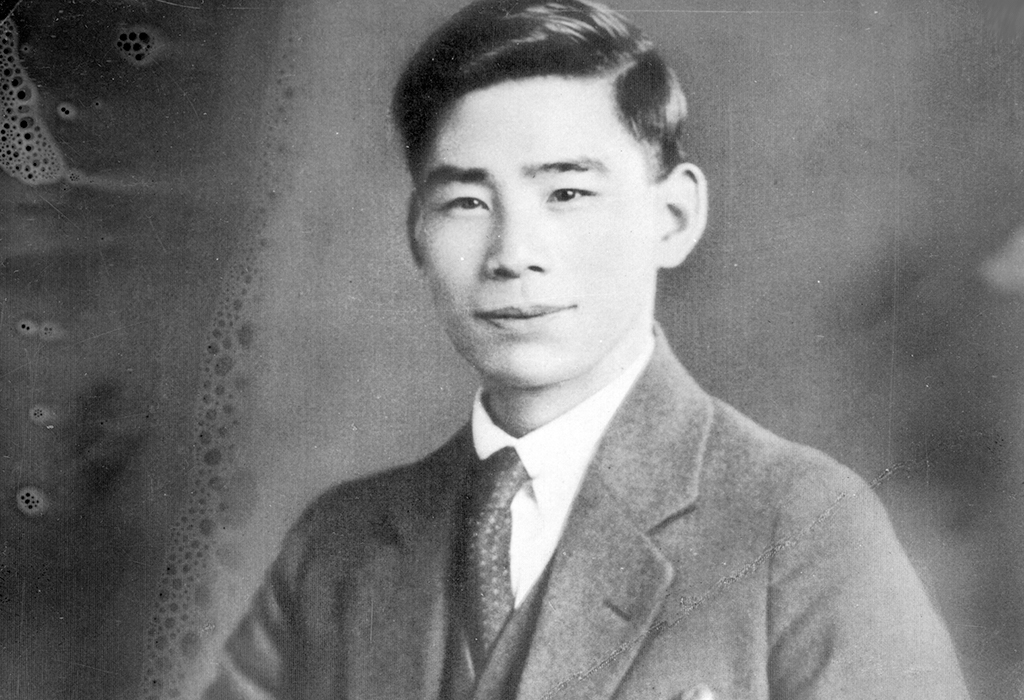

This article was originally published in The Toronto Star on January 26, 2011 as part of a special supplement celebrating the Chinese New Year. It’s the story of Wong Dong Wong who came to Canada as a teenager in 1911 to work in his uncle’s restaurant in Vancouver. He was an orphan with no future in China but he made one for himself in Canada, migrating East to Toronto in 1917 to work as a domestic cook during the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act in Canada. He was hired by my grandfather in 1928. You can download a PDF version of the piece (78Kb).

I was probably a couple of days old when I first met Wong Dong Wong. From then on he was part of my life, someone I was always in touch with and saw regularly until he died 25 years later. My earliest memories include him, and, throughout my childhood, he was a source of unending magic.

Example: The drawer in the kitchen mysteriously stocked with contraband goods — comics, candy and chewing gum. Example: The May 24 fireworks extravaganza he put on in the back garden attracting half the neighbourhood, the crowd expanding each year until the Forest Hill Police dropped by to investigate.

He could mend bikes, do string games and make ice cream; he played gymnastics endlessly with us in the back yard, and he took me to see my first movie.

He could save your bacon by fishing articles out of the storm sewer lost in games of sink-the-battleship in the gutter after a rainfall; but he could also make you shrivel up smaller than Alice-in-Wonderland when your behaviour crossed the line and he issued a summons to the kitchen.

The other side of this idyll, and the reason for Mr. Wong’s presence in our lives, was anything but pleasant. It was the overtly racist immigration laws of the time, specifically the Chinese Exclusion Act in Canada, which condemned thousands of Chinese men to lives of social isolation and targeted injustice in Canada.

Separated from family, often too poor to return to China despite a lifetime of labour, they ended their days, alone in rooming houses.

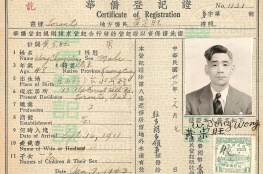

Mr. Wong paid a $500 Head Tax to enter Canada in November 1911.

He was 16, although immigration officials at the port of Victoria decided he was 11, and entered that age in the ledger noting he was 4′ 9” in height and had a scar over his left eye.

He was born in Taishan (Toisan) county in Guangdong in 1895, and brought to Canada as a teenager by a relative who had a job waiting for him in Vancouver.

By 1917, he’d acquired facility in Cantonese as well as English, and had mastered the basics of Canadian (English) cooking. Quite probably he’d also repaid his debt. He then moved to Toronto and found work as a domestic cook which meant fulltime, live-in employment in the homes of white people. He was working for a family in Rosedale when he met my grandfather in the late 1920s.

I began researching Mr. Wong’s life two years ago, using his C.I. 36 certificate to locate him in government records.

Always in my mind, though, was his village in China.

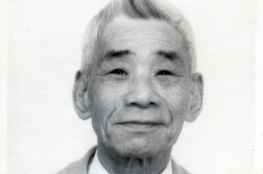

I remember talk about his making the journey home, but it was 1965 before he retired, and he was not in good health. He had worked for my grandparents, latterly my widowed grandmother, for 37 years, and was a great deal more than a cook. He ran the household which included cleaning, laundry and gardening as well as cooking, and when my grandmother reached her 80s and 90s, he was a companion to her.

Undoubtedly Mr. Wong worked longer than he should have.

He stayed because of a promise to my grandfather, and, I suspect, because the Canadian government’s refusal to accept his correct date of birth meant old age benefits were delayed until he was 70. His last years were spent in a rooming house in Chinatown, but not alone. He became close to his neighbour Jim Wong, whom he considered a son. (It was Jim who held Wong’s photo at his funeral in 1970).

When I saw Jim’s son, Tao Wong, recently we shared memories of weekly visits to see grandfather Wong: Tao’s family went on Sundays, my sister Jennie and I on Wednesdays. For 40 years, both families have visited Mr. Wong’s grave.

Wong Dong Wong never returned to China. Almost 100 years after his voyage to Canada, I found myself preparing to make the journey “back” myself.

To write about him, I needed to see his homeland, to experience firsthand, as a friend said, “the richness that must have haunted the memories of Mr. Wong when he looked about his Canadian landscape, and, surely, longed for home.”

I knew I might never find his village, much less the story of how and why he left. Yet, six months into the project, my collaborator in China, Smile Leung, located Wing Ning village, and, last Fall, we travelled there together.

Smile and I met first with the Village Head, Wong Jinhua, who told us we would not find Wong Dong Wong in the official genealogy. Wong was an orphan, whose father had died the month he was born and his mother two years later. His uncle, Wong Wanshen, had felt sympathy for the boy, and so arranged for him to go to Canada. There were no prospects for him in China.

Wong Jinhua introduced us to Wong Wenxi and his family, the descendants of Wong Wanshen. They retold the story of Wong Dong Wong, and showed me a photo of Wong Wanshen, as well as the family’s hand-bound, hand-written record of births going back to 1875.

And there it was, the entry “Wong Zongwong born late in the evening, August 28th, 1895.”

If I make this search sound simple, it wasn’t. I succeeded only because of friends, and the generosity of the Taishanese community, not to mention the perfect strangers who contacted me after an article appeared in Sing Tao daily — Taishan County’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Bureau included.

Christmas is the time my family most remember Mr. Wong. We bake his shortbread, improved, I think, by the encounter with his Chinese savoir-fare.

Over the years, Chinese New Year’s has come to mean something, too. Living next to the Seto family in South Riverdale for 20 years, it was Wong’s Scottish shortbread for Mrs. Seto’s dumplings at the beginning of each lunar year. In Vancouver, a few years ago, it was Todd Wong’s combination Robbie Burns’ Day/Chinese New Year banquet Gung Haggis Fat Choy.

New Year’s for me this year is a time to celebrate the remarkable Mr. Wong.

Susan Crean is a Toronto writer and recipient of a Chalmers Arts Fellowship, which made the trip to Taishan possible. More of Mr. Wong’s story can be found on her website: www.whatistoronto.ca