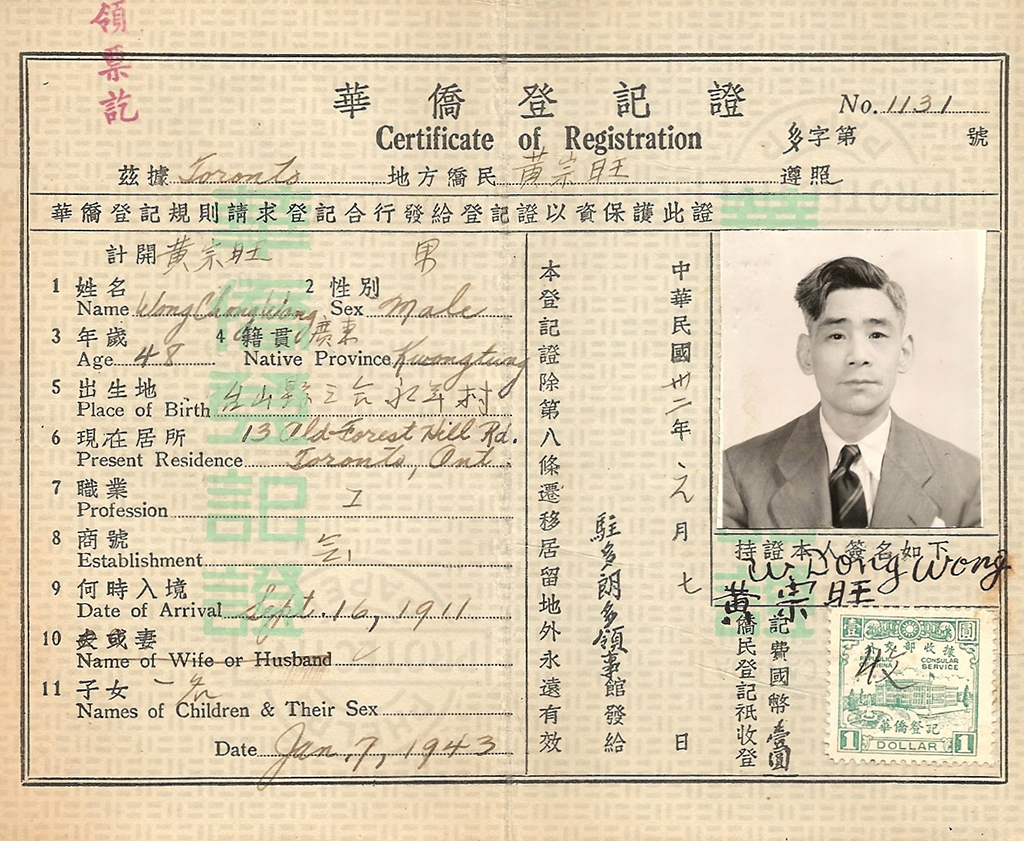

This article by a staff writer was originally published in Sing Tao September 18, 2010, and later reprinted in Kang He magazine. You can also download the article as a PDF (6.1Mb). It’s included as part of a series of stories about the search for the family of Wong Dong Wong, who paid the Chinese head tax to come to Canada. The translation below is by Shan (Joanna) Qiao.

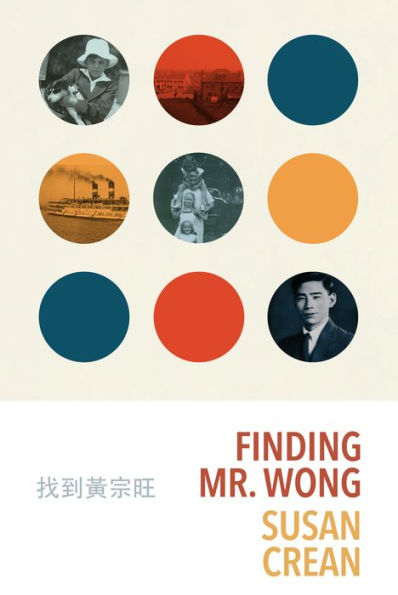

Canadian writer of Irish descent Susan Crean is searching for the past of a long deceased family servant, the Chinese Head Tax payer Wong Dong Wong, a kind and influential member of her family who is still remembered [forty years later].

Born and raised in a middle class family in Toronto’s Forest Hill, Susan studied and travelled in Europe and U.S. in her twenties. She has published several books and served as Chair of The Writers’ Union of Canada in the 1990s.

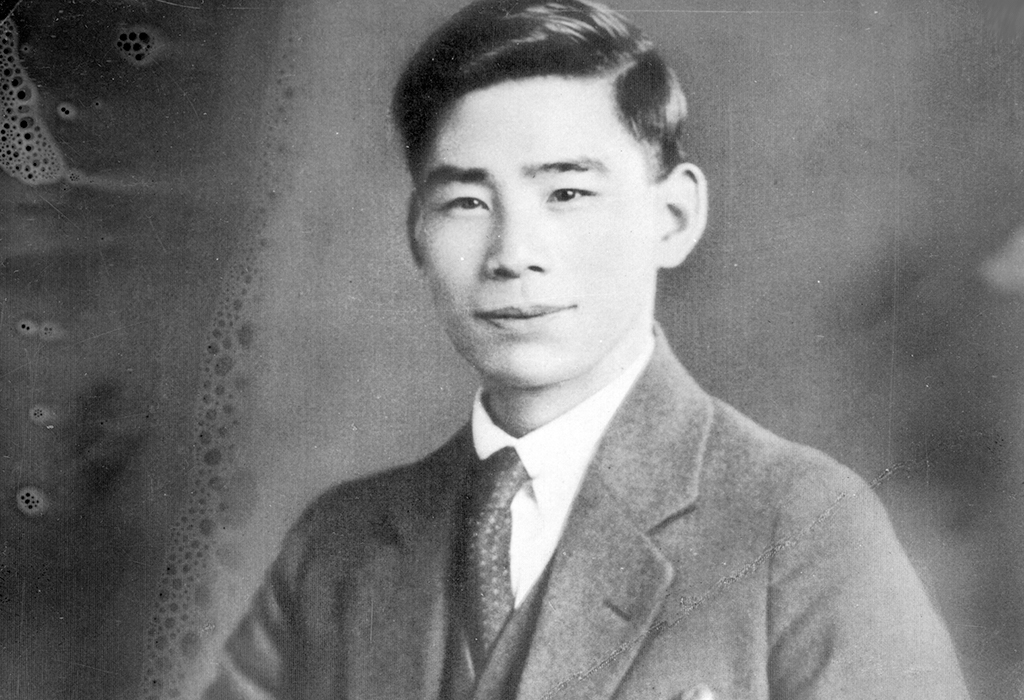

Wong, on the other hand, was a Chinese labourer who struggled to make a life under Canada’s Exclusion Act. Study and travel was beyond his imagination. Because of legal restrictions and financial limitations, his start in life was a one-way ticket to Canada.

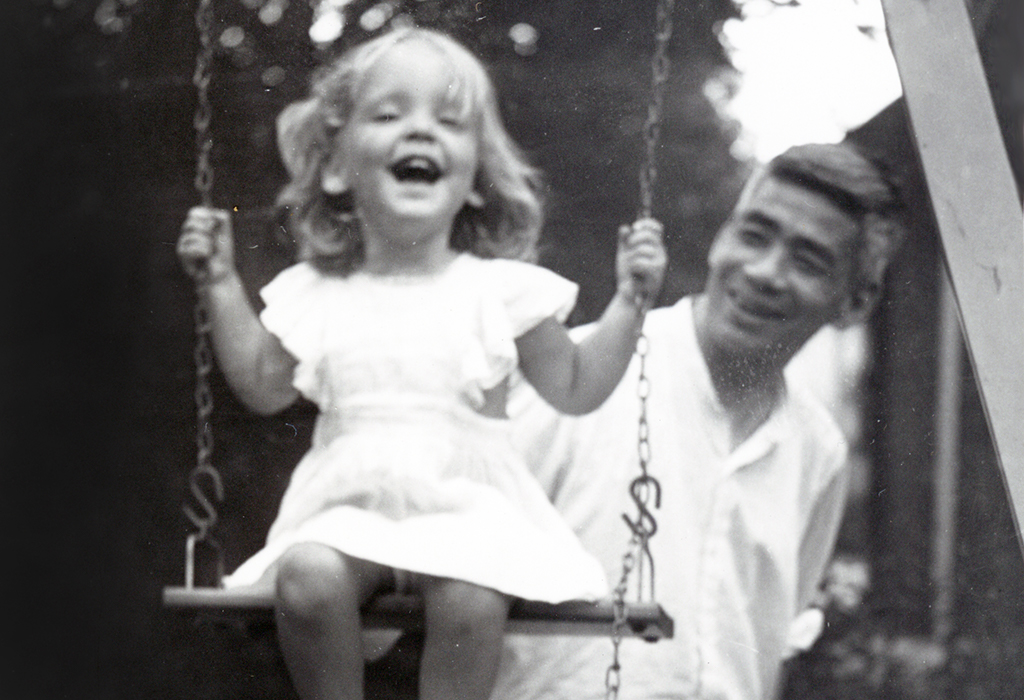

Growing up with Wong in her grandmother’s old kitchen, young Susan would not have known about his past, or how terribly the Head Tax affected his life. In her child’s eyes, Wong was part of the family, and worth fighting for when other white kids called him “Chink”.

Born in 1895, Wong came from a large village called Yong Nian of Tai Shan Province in Southeast China. He followed in the steps of a great many local Taishanese who bought boat tickets, paid the $500 Head Tax, and left for a better life.

Mr. Wong landed in Victoria on November 16th, 1911. He was sixteen and started his life in Gold Mountain unaware he would never get a chance to return home or have a family of his own in his adopted land. In 1928, he moved to Toronto and was hired by Crean’s grandparents as a domestic cook.

As a trusted family servant, Wong was at the deathbed of Crean’s grandfather, and played in the park with Susan and her siblings. He stayed on duty, fulfilling his responsibilities for almost four decades, looking after three generations of the family.

Wong is there in Crean’s childhood memories, a consoling and positive presence. He kept her Grandmother’s house and cooked the meals to perfection, and kept a proper distance with his employer and white society. He was generous at Christmas, and a whiz at fixing bicycles which meant he was popular with the children in the neighbourhood. He was also reserved. He had his dos and don’ts at the house. For example he’d never discussed his private life unnecessarily, or cooked Chinese food, or brought any of his countrymen to the house — not even a lady or companion.

So far as Crean knows, Wong was single and childless. Even though he occasionally mentioned to her father that he had someone back in the village, she never saw any photos or letters from family.

She still remembers some of the stories Wong told them they were young. “He told us about being an orphan, and how once he’d lost his way in the fog while tending his uncle’s cow. He’d been terribly afraid, but the cow knew her way, and guided him back home through the night.

“Wong wasn’t by himself in Chinatown. However, he never brought friends or acquaintances to us. Sometimes, I did hope that he had a regular family life like anybody else does,” she says.

Working as a domestic servant in the fifties and sixties, Wong had a stable and decent job and it would have been possible to save some money at the end of the year. Gambling in underground casinos in Chinatown was a popular way for old Chinese bachelors to kill time. Susan learned later that Wong either sent the money back to the village, or spent it on the gambling table, for he died with very little.

“He was a very generous man. I knew he was sending extra money to China for the education of the next generation,” Crean adds.

At the age of 70, Wong retired from his work and moved to a rooming house with other Chinese bachelor seniors. “I was studying in Europe, and not able to see him a great deal after he retired. However, my sister Jennie made efforts to visit him regularly. After seeing the cockroaches and mice in the first rooming house, she helped him move to 177 Dundas St. West. That was where Wong lived for the rest of his life,” she adds.

Crean visited him every Wednesday with Jennie during her stays in Toronto. They’d hang out at some legendary Chinese restaurant — like Sam Woo ((Sai Woo was located at the time at 130 Dundas St. West. it closed in 2000.)) down the street — enjoying the food Wong wasn’t able to make at her grandparents’ house.

Wong became sick in 1969. Unable to care for himself, he spent his last three months in the hospital and he passed away there on the August long weekend, 1970 at the age of 75. He didn’t leave any written will. Jennie was the one whom the hospital called. He’d left a few hundred dollars, as if he’d figured out how much would cover his funeral expenses and a gravestone. The money was hidden in a tensor bandage that he used to wrap his ankles and legs with as he was a long-time sufferer of varicose veins. The bandage had already been cleared from the room when Jennie arrived, but she managed to find it in the laundry.

Wong was looked after by Jennie and Mr Jim Wong, a younger generation Taishanese who lived next door. Yet no family was there at the end. He was buried not far from his old employers at Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery. The little square gravestone is hardly big enough to tell the story a Head Tax payer and the solitude he endured his entire life.

As both a beloved member of the family and a Chinese Canadian pioneer, Wong is a character whom Susan wants to include in her current book on Toronto. She talks about the hidden history of those pioneers from distant continents, people of different colours and cultures and how diversity has contributed to the creation of the city we now call Toronto.

In order to find out something about Wong’s kin and the place he came from, Crean will be travelling to Taishan, China at the end of September. She will reverse the route that Wong took when made his journey almost a century ago.

Should readers have any information on Wong or his family, please contact Susan Crean.

Sidebar: How Much Was the Chinese Head Tax?

Wong Dong Wong would not have be able to imagine the Canadian government officially apologizing for its past mistake in legislating the Chinese Head Tax. It is equally hard for us to imagine the extreme conditions the Chinese Head Tax payers faced in Canada:

- The amount of Head Tax increased from $50 in 1885 to $100 in 1900. It was increased again to $500 in 1903, equivalent to two years wages of a Chinese labour at the time.

- Meanwhile, Chinese were denied Canadian citizenship. In all, the Federal Government collected $23 million from the Chinese through the Head Tax, equivalent to more than $1.5 billion nowadays.

- In 1923, the Canadian Parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act excluding all but a few Chinese immigrants from entering Canada. Between 1923 and 1947 when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, less than 50 Chinese were allowed to settle in Canada.

- In addition to the Head Tax and Exclusion Act, Chinese immigrants, especially the men, faced other forms of discrimination in their social, economic and political lives. They are not allowed to bring their family, including their wives, to Canada. As a result, the Chinese Canadian community became a “bachelor society”. Exclusion Act resulted in long period of separation of families. Many Chinese families did not reunited until years after the initial marriage, and in some cases they were never reunited.

- The Chinese labourers struggled to make a living in Canada. Unskilled worker’s daily wage was from 5 cents to 10 cents, while skilled workers made about 20 cents a day. Their monthly salary was between $20 and $30. The family workers made between $10 and $30.

- Stephen Harper’s minority government officially apologized for the Chinese Head Tax on June 22nd, 2006, promising to compensate all living Head Tax payers or their widows $20,000.

- According to the statistics made by Chinese Canadian National Council, there were over 2,000 living Head Tax payer across Canada in 1984, however, in 2006, over 90 per cent of them passed away. Only 35 Head Tax payers and 391 widows were able to receive the compensation.

(Information from the website of the Chinese Canadian National Council)