A tale of A Simple Life in Canada

A white female writer’s search in Taishan

A tribute to her servant’s unfinished dream

This piece by Lu Wong, who reports from Vancouver for Sing Tao, appeared in Sing Tao Daily on September 18th, 2010. You can also download it as a PDF (3.2 Mb). This translation is by Shan (Joanna) Qiao and is part of a series of Chinese head tax stories.

A tale of a man much like the one depicted in Hong Kong’s award-winning movie A Simple Life is happening here in Canada. Former Chair of The Writer’s Union of Canada Susan Crean started her trip to Taishan, China last year in search of the untold story of Wong Chong Wong, her family servant for 37 years.

Susan went to Yong Ning Village, Taishan, Guangdong province last September, hoping to meet with Wong’s descendants, find his family genealogy and learn his past as an orphan.

The relationship of Susan and Wong was as close as a family. She took care of Wong before he passed away a true reflection of the award-winning Hong Kong movie A Simple Life.

Susan says she will continue to search and collect Wong’s information and start to write stories of people like him and other family servants in Canada. She wants to unfold the hardship of Chinese labourers who came to Canada more than a century ago.

Serving the Crean family for four generations

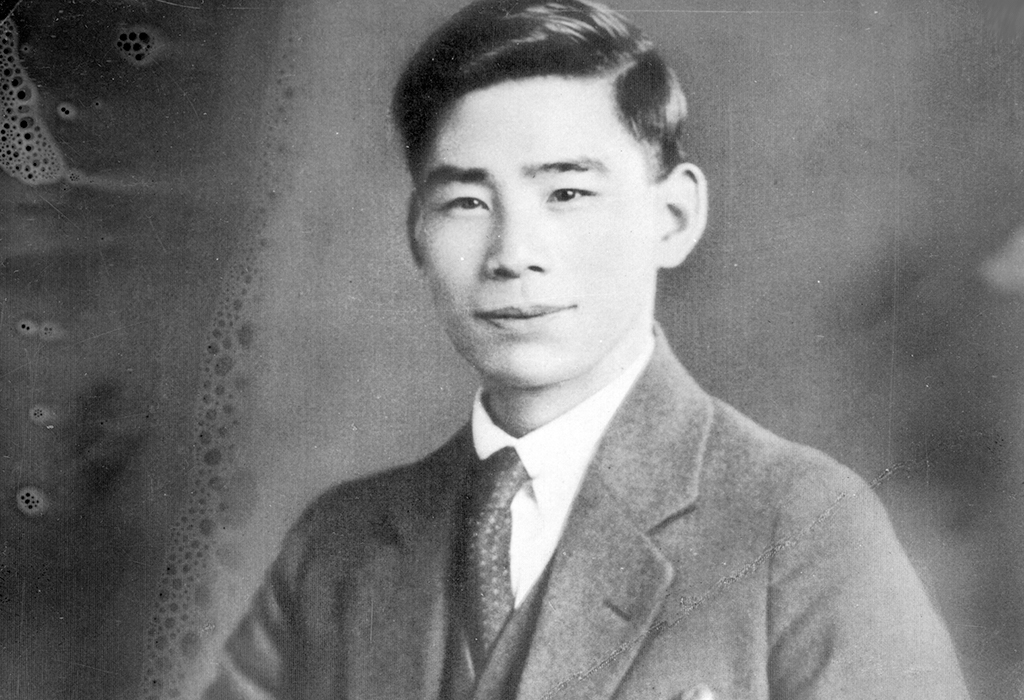

67-year-old Susan is an acclaimed Canadian writer. She remembers that Wong was 50 years old when she was born. In her memory, Wong was no different than her family members.

Originally from Canton province, China, Wong paid the Chinese head tax and came to Canada in 1911. With the help from his uncle Ru Wen Wong, he started working in Vancouver. He came to Toronto in 1917 and was hired by Susan’s grandfather in 1928. Wong started his lifelong work as a servant in Susan’s family then. He passed away in 1970 at the age of 75.

Last September when Sing Tao first told the story of Susan and Wong, many of our readers contacted Susan and provided her with useful information related to Wong and his family.

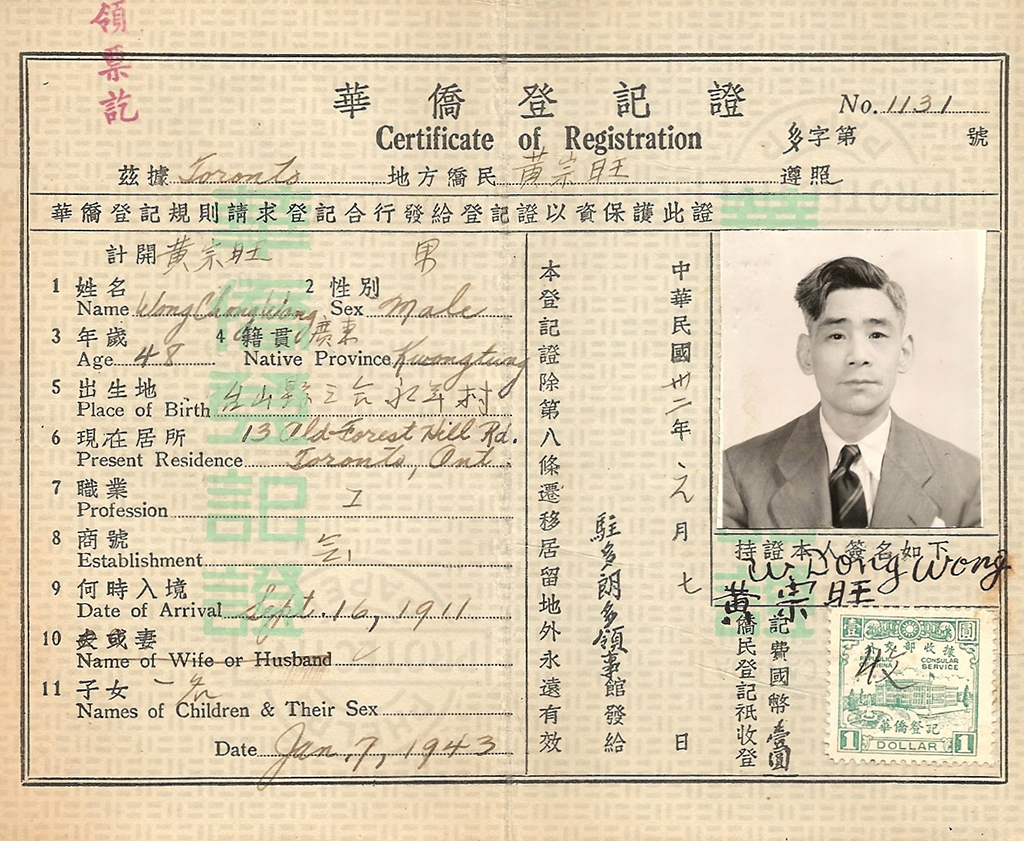

With the help from several Chinese Canadian history researchers and Vancouver friend Hou Ji Chen (Howe Chan), Susan started her trip to Wong’s birth place, a village called Yong Nian in Taishan. The only official documents identified Wong that Susan has were a piece of immigration paper issued by Canada government and the registration paper Chinese government issued to overseas Chinese in 1940.

Chinese head tax stories: Looking for the descendants in Canton Province

With the village head Jinhua Huang’s help, Susan learned that Wong’s father were died before he was born. His mother passed away two years after. Being an orphan, Wong was under the care of his uncle Ru Yun Wong and eventually followed his uncle’s footstep to Vancouver in 1911.

Wong went to Toronto in 1917. He met Susan’s grandfather and worked as cook and servant since then.

During her stay in Canton, Susan also visited the grandson of Wong’s uncle, Wen Xi Wong. With the help from Wong’s descendants and Hou Ji Chen, she found the genealogy book of Yong Nian village and Wong’s family.

On the genealogy book, it showed the name of Wong’s father as Ru Zhen Wong. Followed that line was the name of Wong, yet replaced by the character “和(he)”.

Looking at the old house Wong used to live, Susan was glad that she was able to pay the last tribute to Wong. With more stories of Chinese domestic workers to be heard, she will continue her research on this particular history of Chinese Canadian.

Sidebar I: Wealthy white family hired houseboy

According to writer Susan’s research, there were many Chinese flocked to Vancouver to build Canadian Pacific Railway between 1881 and 1885. They also created a new local industry, domestic servants. Discriminated by white people, they were generally called “Chinamen” or “houseboy”.

Most of the house servants came to Canada or America in their teenage ages. Not understanding any English, they were introduced to work at white families as cook helper, then they learned laundry, ironing, gardening and babysitting gradually at work. They managed to save some money from the meager earnings and sent back to their families in China.

Normally only wealthy families were able to hire houseboys in Canada. Hence this is one way to show the status of the family at that time. If the houseboy works well, he would be promoted from seasonal helper to a family servant that worked like a butler who takes responsibility to run the family.

Some family servants carefully saved their earnings and opened a restaurant or laundry store after they retired.

Sidebar II

Directed by Ann Hui, A Simple Life is an award-winning Hong Kong movie starring Andy Lau and Deanie Ip. Ah Tao is a family servant and nanny who started working for the Leung family when she was 13 years old. Six decades passed, she has served five generations. As time goes by, some family members passed away and some immigrated. She lives with Roger, the son and the only family members of the Leung.

Although two of them rarely talk, they enjoy the company of each other. One day Ah Tao unexpectedly suffers a stroke, Roger has to send her to senior house for more care. The strong relationship between the employer and his servant is slowly unveiled.

The movie was nominated for the Best Movie at the 68th Venice Film Festival in 2011. Deanie Ip won Best Actress at the Festival and has become the first Hong Kong actress who won the award.

Sidebar III: Remembered as a grandfather

Although discrimination against Chinese people was normal at the time when Susan grew up, she looked at Wong as one of her family members and asked him to be in her family photos. Whenever Susan misses Wong, she would take out the family photo to reminisce him.

“I literally grew up in Wong’s kitchen. He was like my grandfather and I enjoyed his company very much,” says Susan.

She remembers Wong was always around when she was little and let her ride on his shoulders. She even respected Wong as her grandfather and was never shy to show her fondness and curiosity to Wong.

Susan says that Wong cooked excellent food for the family and were good at making both western food and Chinese food. His bicycle repair skills were quite well known in the neighbourhood. It was impressive to her that Wong was the type that never hesitates to offer help whenever needed.

Wong retired in 1964 and moved out to Chinatown. Susan and her sister Jennie visited him frequently.

“It was such a regret that the last time I talked to him was actually through a phone call. I regret that I was not able to see him when he died. I’ll always remember him like my grandfather,” says Susan.